Union Army's Irish Brigade

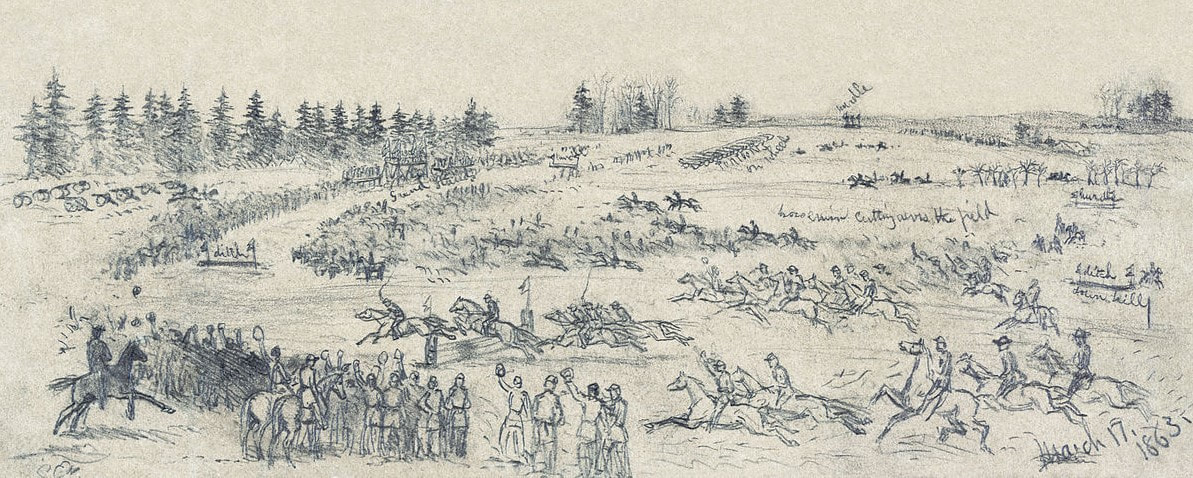

"The Great St. Patrick's Day Steeplechase"

On March 17, 1863, Josiah Marshall Favill, a young lieutenant in the 57th New York Infantry, was one of many soldiers in the Army of the Potomac to observe the elaborate St. Patrick's festivities being hosted by General Thomas Francis Meagher and the men of the Irish Brigade. When he returned to his regiment's camp later that day, Favill recorded the following observations in his diary:

“This being St. Patrick’s day, or the 17th of Ireland, as the men call it, General Meagher and staff celebrated by giving a steeplechase on the parade ground of the division. A course was carefully laid out, ditches dug, hurdles erected, and valuable prizes offered to the contestants. The conditions were simply that none but commissioned officers of the division could ride, which was sufficiently liberal. A crowd of officers presented themselves aspirants for honors, as well as prizes. Meagher, glorious in fancy undress uniform liberally covered with gold braid, and followed by a jolly lot of staff officers, rode about the course, master of all he surveyed. He is a very good horseman. Most of the general officers of the army, with their many lady friends, were invited, resulting in a magnificent crowd. Amongst many notables riding in the train of the commander-in-chief, was the Princess Salm Salm, a beautiful and fearless horse woman. When she first came on the ground, she rode her horse up to a five foot hurdle and nonchalantly took a standing jump, clearing it handsomely. [Major General Joseph] Hooker looked superb, followed by a great crowd of staff officers and retinue of mounted ladies.

“This being St. Patrick’s day, or the 17th of Ireland, as the men call it, General Meagher and staff celebrated by giving a steeplechase on the parade ground of the division. A course was carefully laid out, ditches dug, hurdles erected, and valuable prizes offered to the contestants. The conditions were simply that none but commissioned officers of the division could ride, which was sufficiently liberal. A crowd of officers presented themselves aspirants for honors, as well as prizes. Meagher, glorious in fancy undress uniform liberally covered with gold braid, and followed by a jolly lot of staff officers, rode about the course, master of all he surveyed. He is a very good horseman. Most of the general officers of the army, with their many lady friends, were invited, resulting in a magnificent crowd. Amongst many notables riding in the train of the commander-in-chief, was the Princess Salm Salm, a beautiful and fearless horse woman. When she first came on the ground, she rode her horse up to a five foot hurdle and nonchalantly took a standing jump, clearing it handsomely. [Major General Joseph] Hooker looked superb, followed by a great crowd of staff officers and retinue of mounted ladies.

The race was a great success, there being many falls, many horses injured and a lot of riders. Wilson, of Hancock’s staff, rode, although getting one or two bad falls, managed to pull through, and win one of the prizes. Jack Garcon the O’Malley dragoon aide, won first prize and was fully entitled to it. The course was surrounded by thousands, kept in order by guards posted entirely around the field. In the evening General Meagher gave a reception, and of course, all the brigade and other commanders, with their staffs, were invited. Zook, Broom, and I attended, but the pace was too fast for Zook and so we retired early, leaving Broom, who is quite equal to every emergency of this sort, to do the honors.

Within a large hospital tent, mounted upon a table in the center, stood an immense punch bowl filled to the brim with the strongest punch I ever tasted. All were invited to partake and such a gathering of jolly, handsomely dressed fellows, I never saw before. The Irish brigade was in its glory. It understood the situation, was master of it, and quite immortalized itself".

Within a large hospital tent, mounted upon a table in the center, stood an immense punch bowl filled to the brim with the strongest punch I ever tasted. All were invited to partake and such a gathering of jolly, handsomely dressed fellows, I never saw before. The Irish brigade was in its glory. It understood the situation, was master of it, and quite immortalized itself".

And this was St Patrrick's Day, after all, so in true fashion, the spitits overcame good judgement! Lt. Favill goes on to write in his diary:

"There was the inevitable quarrel. How could it, otherwise, have been complete? The general and the brigade surgeon ended in challenging each other to mortal combat, and for a time matters assumed a threatening aspect. The following morning, however, when the effects of the nectar had subsided, the surgeon apologized in due form, and peace resumed her loving sway.

Mitchell, of Hancock’s staff, was in high feather, and might easily have been mistaken for one of the festive brigade.”

Mitchell, of Hancock’s staff, was in high feather, and might easily have been mistaken for one of the festive brigade.”

Irish Brigade

The Irish Brigade was an infantry brigade, consisting predominantly of Irish Americans, who served in the Union Army in the American Civil War. The designation of the first regiment in the brigade, the 69th New York Infantry, or the "Fighting 69th", continued in later wars. The Irish Brigade was known in part for its famous war cry, the "Faugh a Ballaugh", which is an anglicization of the Irish phrase, fág an bealach, meaning "clear the way" and used in various Irish-majority military units founded due to the Irish diaspora. According to Fox's Regimental Losses, of all Union army brigades, only the 1st Vermont Brigade and Iron Brigade suffered more combat dead than the Irish Brigade during America's Civil War.

Fun Facts About St. Patrick's Day

Maybe one of the most surprising things to visitors to the US is how excited everyone seems to get for St. Patrick’s Day. Why, they wonder, Americans so eager to celebrate a religious holiday from another country?

The history of St. Paddy’s Day in America is a fascinating one. So pour yourself a green beer (or a nice mug of Irish breakfast tea, depending on your preference), and let’s delve into the extraordinary history of the wearin’ o’ the green here in the US.

Fact: St. Patrick’s Day has been celebrated in the US for a long time

As a matter of fact, the very first St. Patrick’s Day parade was actually celebrated stateside. It wasn’t even celebrated by the Irish. In fact, it happened in a Spanish colony in what is today St. Augustine, Florida!

Their chaplain, Ricardo Artur, was Irish, and in 1601, he organized a parade on March 17th in honor of his home country’s patron saint. He was evidently quite devoted to St. Patrick, because records show that he held a St. Patrick’s Day celebration the year before, too.

Fact: Saint Patrick wasn’t even Irish!

The idea that “everyone’s a little bit Irish on St. Patrick’s Day” could extend to the patron saint of Ireland himself, who wasn’t actually a native son of the Emerald Isle. Patrick was born in Britain in the 4th century, the son of wealthy Romans. It wasn’t until he was kidnapped by pirates at 16 that he even set foot in Ireland.

Patrick was enslaved and worked as a shepherd. It was during this difficult time that he became religious, and even though he managed to escape home with some sailors in the year 408, he was determined to return to Ireland to convert the country to Christianity.

Fact: St. Patrick is why the shamrock is an Irish icon

He eventually realized this goal, coming back as a Catholic bishop and converting people through preaching, writing, and incorporating the pagan symbols the Irish were used to in order to explain theological concepts.

Tradition holds that Patrick used the three-leaved shamrock to explain the Christian doctrine of the Holy Trinity to the Irish.

Fact: Why green?

Of course, everyone knows Ireland is famous for its lush green hills. However, green came to be especially associated with Ireland during the country’s struggle for independence from Britain.

The feast of St. Patrick has always been observed by faithful Catholics in Ireland on March 17th, who like most saints, is celebrated on the day he is believed to have died. As the patron saint of Ireland, they recognize Patrick as a special intercessor and spiritual protector of the country, usually by going to church on March 17th.

In the wake of the Irish independence movement that began in earnest in the 1700s, green came to be the color of the Irish nationalists, who sought self-governance separate from England.

Fact: St. Patrick’s Day: Made in the USA

The idea of St. Patrick’s Day as a party is uniquely American. No less a personage than George Washington held a St. Patrick’s Day celebration for his troops during the Revolutionary War. Many of them were Irish, and he thought it might boost morale during an epically cold winter in 1780.

However, Irish troops serving in the British Army held a St. Paddy’s Day parade in New York City as early as the 1760s, marching past Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral, a tradition that continues in the city’s parade to this day (except, obviously, 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic). An even earlier parade, Boston first celebrated Saint Patrick’s Day in 1737 as a gesture of solidarity among the city’s Irish immigrants. In 1901, its parade moved to South Boston and became a dual celebration also commemorating Evacuation Day, when residents forced the evacuation of British troops from the city in 1776.

With a wave of Irish immigrants in the 19th century, St. Patrick’s Day became a way for homesick and often discriminated-against Irish to celebrate their heritage. After their service to the Union Army during the Civil War, attitudes toward the Irish began to shift, and more Americans began to join in the St. Paddy’s Day fun.

The history of St. Paddy’s Day in America is a fascinating one. So pour yourself a green beer (or a nice mug of Irish breakfast tea, depending on your preference), and let’s delve into the extraordinary history of the wearin’ o’ the green here in the US.

Fact: St. Patrick’s Day has been celebrated in the US for a long time

As a matter of fact, the very first St. Patrick’s Day parade was actually celebrated stateside. It wasn’t even celebrated by the Irish. In fact, it happened in a Spanish colony in what is today St. Augustine, Florida!

Their chaplain, Ricardo Artur, was Irish, and in 1601, he organized a parade on March 17th in honor of his home country’s patron saint. He was evidently quite devoted to St. Patrick, because records show that he held a St. Patrick’s Day celebration the year before, too.

Fact: Saint Patrick wasn’t even Irish!

The idea that “everyone’s a little bit Irish on St. Patrick’s Day” could extend to the patron saint of Ireland himself, who wasn’t actually a native son of the Emerald Isle. Patrick was born in Britain in the 4th century, the son of wealthy Romans. It wasn’t until he was kidnapped by pirates at 16 that he even set foot in Ireland.

Patrick was enslaved and worked as a shepherd. It was during this difficult time that he became religious, and even though he managed to escape home with some sailors in the year 408, he was determined to return to Ireland to convert the country to Christianity.

Fact: St. Patrick is why the shamrock is an Irish icon

He eventually realized this goal, coming back as a Catholic bishop and converting people through preaching, writing, and incorporating the pagan symbols the Irish were used to in order to explain theological concepts.

Tradition holds that Patrick used the three-leaved shamrock to explain the Christian doctrine of the Holy Trinity to the Irish.

Fact: Why green?

Of course, everyone knows Ireland is famous for its lush green hills. However, green came to be especially associated with Ireland during the country’s struggle for independence from Britain.

The feast of St. Patrick has always been observed by faithful Catholics in Ireland on March 17th, who like most saints, is celebrated on the day he is believed to have died. As the patron saint of Ireland, they recognize Patrick as a special intercessor and spiritual protector of the country, usually by going to church on March 17th.

In the wake of the Irish independence movement that began in earnest in the 1700s, green came to be the color of the Irish nationalists, who sought self-governance separate from England.

Fact: St. Patrick’s Day: Made in the USA

The idea of St. Patrick’s Day as a party is uniquely American. No less a personage than George Washington held a St. Patrick’s Day celebration for his troops during the Revolutionary War. Many of them were Irish, and he thought it might boost morale during an epically cold winter in 1780.

However, Irish troops serving in the British Army held a St. Paddy’s Day parade in New York City as early as the 1760s, marching past Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral, a tradition that continues in the city’s parade to this day (except, obviously, 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic). An even earlier parade, Boston first celebrated Saint Patrick’s Day in 1737 as a gesture of solidarity among the city’s Irish immigrants. In 1901, its parade moved to South Boston and became a dual celebration also commemorating Evacuation Day, when residents forced the evacuation of British troops from the city in 1776.

With a wave of Irish immigrants in the 19th century, St. Patrick’s Day became a way for homesick and often discriminated-against Irish to celebrate their heritage. After their service to the Union Army during the Civil War, attitudes toward the Irish began to shift, and more Americans began to join in the St. Paddy’s Day fun.

George Washington's

St Patrick's Day Orders

When General George Washington needed to boost sagging patriot morale, he enlisted a rarely celebrated holiday—St. Patrick’s Day—to the cause.

The Continental Army that encamped in Morristown, New Jersey, shivered through the brutal winter of 1779-1780. It was hard for them to believe that conditions could be any harsher than they had been at Valley Forge two years prior, but these were truly the cruelest days of the American Revolution. Twenty-eight separate snowstorms struck the encampment, burying it under as much as 6 feet of snow, between November 1779 and April 1, 1780. Through the coldest winter in recorded history, patriot foot soldiers slept on straw and huddled together for warmth in rudimentary log huts. The weather made it difficult to obtain supplies, and men went days without food. Some even resorted to eating the bark off twigs for nourishment.

Needless to say, frivolity was at a severe premium. George Washington knew he needed to buoy the spirits of his forces, so he did what a good boss would do: he gave them a day off. The general granted his troops just a single holiday that winter in Morristown, and it wasn’t Christmas. It was a holiday rarely observed in America—St. Patrick’s Day.

The Irish represented the largest immigrant group to arrive in the colonies in the 1700s. The first St. Patrick’s Day celebration in Colonial America dated back to 1737 in Boston, but commemorations of the feast day of Ireland’s patron saint were limited by the time of the American Revolution. The Irish who had immigrated to Colonial America were mainly Presbyterians from the northern province of Ulster. (Irish Catholics would not begin to arrive in large numbers until the Great Famine of the 1840s.) These “Scotch-Irish,” driven from Ireland by British oppression in the first place, were predisposed to support the rebellion against the crown. Estimates are that one-quarter or more of the Continental Army was Irish by birth or ancestry, and regiments from Pennsylvania and Maryland were nearly half-Irish. Generals born in Ireland or who had Irish parents commanded seven of the eleven brigades wintering in Morristown.

Back in Ireland—which, like America, was striving for independence from the yoke of the British Empire—the populace was naturally sympathetic to the patriot cause during the American Revolution. The Irish in Ulster were so open in their support that the lord lieutenant of Ireland complained to London that the Irish Presbyterians were “in their hearts” Americans who were “talking in all companies in such a way that if they are not rebels, it is hard to find a name for them.”

So in an effort to give his men a badly needed break, to recognize the heritage of many of his soldiers and to express solidarity with the “brave and generous” people of Ireland, Washington issued general orders on March 16, 1780, proclaiming St. Patrick’s Day a holiday for his troops. It was the first day of rest for the Continental Army in more than a year. “The General directs that all fatigue and working parties cease for to-morrow the SEVENTEENTH instant,” read the orders, “a day held in particular regard by the people of Ireland.”

Washington also told his troops that he expected “that the celebration of the day will not be attended with the least rioting or disorder.” While not all St. Patrick’s Day celebrations are well-behaved affairs, it appears that this one was. Soldiers may not have quaffed green tankards of ale, but the men of the Pennsylvania Division at least enjoyed a hogshead of rum that had been purchased by their commander. In appreciation of his actions, the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, a relief organization for Irish immigrants, named Washington an honorary member in 1782.

The date of St. Patrick’s Day already held special significance for Washington. Four years prior, on March 17, 1776, the British evacuated Boston, and the general had his first major strategic victory since assuming the command of the Continental Army in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in July 1775. Nearly 9,000 Redcoats and more than 1,000 Loyalists boarded 120 ships in Boston Harbor on that St. Patrick’s Day morning, and the enormous flotilla set sail for Halifax, Nova Scotia. Legend has it that Washington selected “Boston” as the password for the first troops to re-enter the town that day, and, in honor of Ireland’s patron saint, “St. Patrick” was the proper response.

March 17 is today a civic holiday in Boston, ostensibly to commemorate “Evacuation Day.” But much like Washington’s army holed up in Morristown, most Bostonians spend the day celebrating all things Irish—with or without a hogshead of rum.

The Continental Army that encamped in Morristown, New Jersey, shivered through the brutal winter of 1779-1780. It was hard for them to believe that conditions could be any harsher than they had been at Valley Forge two years prior, but these were truly the cruelest days of the American Revolution. Twenty-eight separate snowstorms struck the encampment, burying it under as much as 6 feet of snow, between November 1779 and April 1, 1780. Through the coldest winter in recorded history, patriot foot soldiers slept on straw and huddled together for warmth in rudimentary log huts. The weather made it difficult to obtain supplies, and men went days without food. Some even resorted to eating the bark off twigs for nourishment.

Needless to say, frivolity was at a severe premium. George Washington knew he needed to buoy the spirits of his forces, so he did what a good boss would do: he gave them a day off. The general granted his troops just a single holiday that winter in Morristown, and it wasn’t Christmas. It was a holiday rarely observed in America—St. Patrick’s Day.

The Irish represented the largest immigrant group to arrive in the colonies in the 1700s. The first St. Patrick’s Day celebration in Colonial America dated back to 1737 in Boston, but commemorations of the feast day of Ireland’s patron saint were limited by the time of the American Revolution. The Irish who had immigrated to Colonial America were mainly Presbyterians from the northern province of Ulster. (Irish Catholics would not begin to arrive in large numbers until the Great Famine of the 1840s.) These “Scotch-Irish,” driven from Ireland by British oppression in the first place, were predisposed to support the rebellion against the crown. Estimates are that one-quarter or more of the Continental Army was Irish by birth or ancestry, and regiments from Pennsylvania and Maryland were nearly half-Irish. Generals born in Ireland or who had Irish parents commanded seven of the eleven brigades wintering in Morristown.

Back in Ireland—which, like America, was striving for independence from the yoke of the British Empire—the populace was naturally sympathetic to the patriot cause during the American Revolution. The Irish in Ulster were so open in their support that the lord lieutenant of Ireland complained to London that the Irish Presbyterians were “in their hearts” Americans who were “talking in all companies in such a way that if they are not rebels, it is hard to find a name for them.”

So in an effort to give his men a badly needed break, to recognize the heritage of many of his soldiers and to express solidarity with the “brave and generous” people of Ireland, Washington issued general orders on March 16, 1780, proclaiming St. Patrick’s Day a holiday for his troops. It was the first day of rest for the Continental Army in more than a year. “The General directs that all fatigue and working parties cease for to-morrow the SEVENTEENTH instant,” read the orders, “a day held in particular regard by the people of Ireland.”

Washington also told his troops that he expected “that the celebration of the day will not be attended with the least rioting or disorder.” While not all St. Patrick’s Day celebrations are well-behaved affairs, it appears that this one was. Soldiers may not have quaffed green tankards of ale, but the men of the Pennsylvania Division at least enjoyed a hogshead of rum that had been purchased by their commander. In appreciation of his actions, the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick, a relief organization for Irish immigrants, named Washington an honorary member in 1782.

The date of St. Patrick’s Day already held special significance for Washington. Four years prior, on March 17, 1776, the British evacuated Boston, and the general had his first major strategic victory since assuming the command of the Continental Army in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in July 1775. Nearly 9,000 Redcoats and more than 1,000 Loyalists boarded 120 ships in Boston Harbor on that St. Patrick’s Day morning, and the enormous flotilla set sail for Halifax, Nova Scotia. Legend has it that Washington selected “Boston” as the password for the first troops to re-enter the town that day, and, in honor of Ireland’s patron saint, “St. Patrick” was the proper response.

March 17 is today a civic holiday in Boston, ostensibly to commemorate “Evacuation Day.” But much like Washington’s army holed up in Morristown, most Bostonians spend the day celebrating all things Irish—with or without a hogshead of rum.